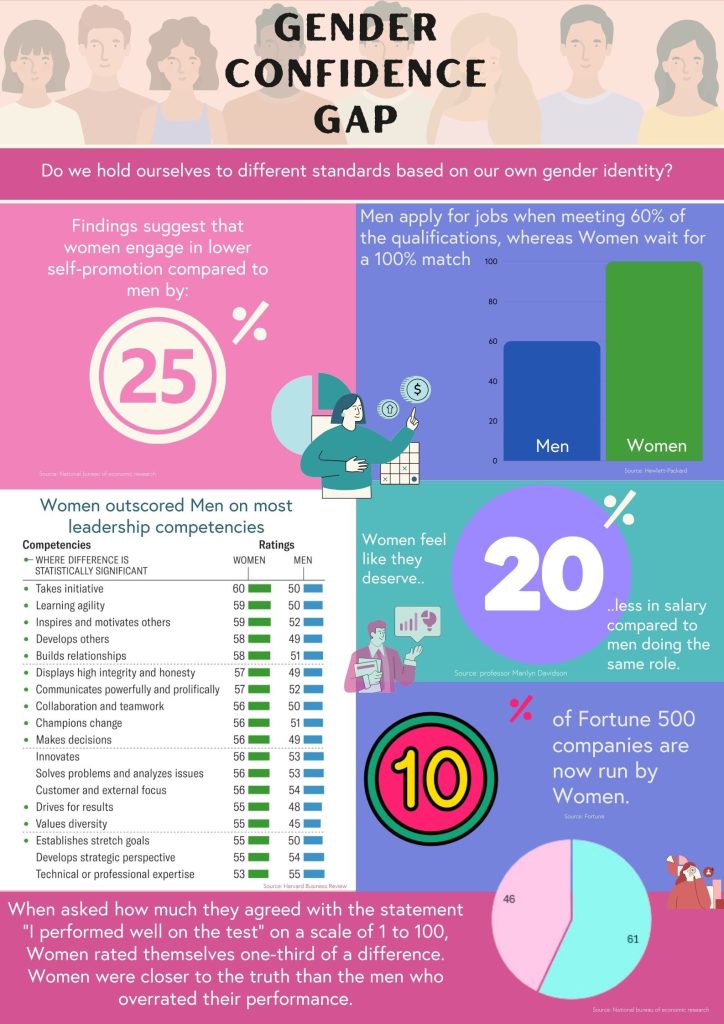

Gender Confidence Gap

4 min read

Studies1 revealed a concerning gender gap in self-promotion, where women consistently rated their performance lower than men, even when their actual achievements were equal.

This gap persisted regardless of participants being informed about their performance or the absence of external pressures like promotion incentives. Interestingly, the gender gap only closes when individuals were asked about the performance of others, rather than themselves, or when participants were asked about a more ‘female-typed task’. 2

These findings suggest the gap might stem from societal norms and expectations influencing women to undervalue their accomplishments, combined with their tendency for stricter self-evaluation compared to men. This disparity can disadvantage women in career advancement and negotiations, highlighting the need for awareness campaigns, addressing harmful stereotypes, and encouraging women to confidently advocate for themselves and their achievements. Further research is crucial to delve deeper into the cultural and social underpinnings of this gap, alongside exploring effective interventions to bridge the divide in self-promotion between genders.

Self-promotion results:

The findings of the recent studies indicate a significant gender gap in self-promotion among equally performing men and women. Here are the specific findings for each of the four self-evaluation questions:

- Performance Question: Women’s average responses are 12.68 points lower than men’s, representing a 24% decrease relative to the mean.

- Performance-Bucket Question: Women’s average responses are 0.59 points lower than men’s, representing a 17% decrease relative to the mean.

- Willingness-to-Apply Question: Women’s average responses are 15.31 points lower than men’s, representing a 31% decrease relative to the mean.

- Success Question: Women’s average responses are 15.08 points lower than men’s, representing a 27% decrease relative to the mean.

These findings suggest that women engage in lower self-promotion compared to men across all four questions, indicating a substantial and statistically significant gender gap in self-promotion. Further analysis in the study investigates the underlying factors contributing to this gap.

The gap when informed about performance:

Even when participants are fully informed about their absolute and relative performance, the gender gap in self-promotion persists. This indicates that the gender gap is not solely driven by differences in performance beliefs but also influenced by other social and psychological factors.

Informed Self-Promotion Gap (0-100 Scale):

- Performance Question: The gender gap in informed self-promotion is 7.01 percentage points.

- Willingness-to-Apply Question: The gender gap in informed self-promotion is 10.73 percentage points.

- Success Question: The gender gap in informed self-promotion is 11.73 percentage points.

- Informed Self-Promotion Gap (1-6 Scale):

- The gender gap in informed self-promotion is 0.40.

- Impact of Information on Gender Gap:

- Information significantly reduces the gender gap in self-promotion by anywhere from 10-31%.

The gap when promotion incentives are removed:

Both men and women respond to these incentives by providing more favourable answers in the Self-Promotion version. However, the gender gap remains similar in both the Private and Self-Promotion versions, indicating that men and women respond to promotion incentives to a similar extent.

The gap when informed of typical responses:

The persistence of the gender gap, even in the absence of promotion incentives and with participants fully aware of their performance, indicates a fundamental disparity in how men and women subjectively assess their own achievements. This suggests that the underlying gender gap may be influenced by perceptions of what is considered typical or socially acceptable.

The gender gap persists even when promotion incentives are removed and participants are fully informed of their absolute and relative performance.

- This suggests that there is an underlying gender gap in how men and women subjectively evaluate their performances.

- The persistence of the gender gap may be influenced by views about what is considered typical or socially appropriate.

- In a second wave of data collection, the gender gap was replicated in both the Private version (where participants were not informed about their performance) and the Private (Social Norms) version (where participants were informed about their performance and the average responses of others with the same performance).

- The gender gap was observed in both versions of the study, regardless of whether participants were informed about their performance or not.

- Informed self-promotion, where participants were provided with information about their performance and the average responses of others, showed a similar magnitude of gender gap in both the Private and Private (Social Norms) versions.

The gap when immediately informed about their performance:

- Consistency motives and anchoring effects can influence the persistence of gender gaps observed in the study versions.

- Participants answer self-evaluation questions before and after being informed about their performance.

- Subjective views about performance are often formed before individuals receive feedback.

- In the third wave of data collection, the gender gap is replicated in the Private version.

- The gender gap exists in the Private version even when participants are informed about their absolute and relative performance.

- The gender gap is also observed in the Private (Immediately Informed) version, where participants are immediately informed about their performance before answering self-evaluation questions.

- The persistence of the gender gap suggests that it exists even when participants are not asked self-evaluation questions before being informed about their performance.

The gap when individuals evaluate others:

- In the Private (Other-Evaluation) version, where participants were informed about another participant’s absolute and relative performance and then asked to evaluate that participant’s performance, small and often statistically insignificant gender gaps were found.

- These findings suggest that gender differences in performance evaluation are more pronounced when individuals evaluate their own performance compared to when they evaluate the performance of others.

- The results align with prior research indicating that women may be more critical of their own performance and underestimate their abilities compared to men.

- The study suggests that women may be better advocates for others in evaluations and negotiations than they are for themselves.

The gap when asked about a more female-typed task:

- when considering data from the female-typed task (verbal test), there are no statistically significant gender gaps, whether participants are aware of their performance or not.

- These findings, along with evidence in Section 3.6, suggest that gender norms and culture play a role in shaping individuals’ views of their own performance.

- The persistence of the gender gap in subjective evaluations of math and science performance indicates that it is not solely driven by women subjectively evaluating performance differently from men in general.

- The absence of a gender gap in self-evaluations of verbal skills or evaluations of someone else’s performance on the math and science test further supports this conclusion.

The findings presented here challenge us to examine our own biases and preconceptions surrounding gender and performance. Do we hold ourselves to different standards based on our own gender identity? How can we create spaces where individuals feel empowered to authentically evaluate their accomplishments without societal pressures? Recognising the confidence gap is only the first step. By engaging in open dialogue, fostering self-awareness, and actively challenging harmful stereotypes, we can collectively work towards closing this gap and building a more equitable future for all.

Author Openside Group

Other sources for information:

Sources: 1 Harvard Business School and Wharton, 2 National bureau of economic research